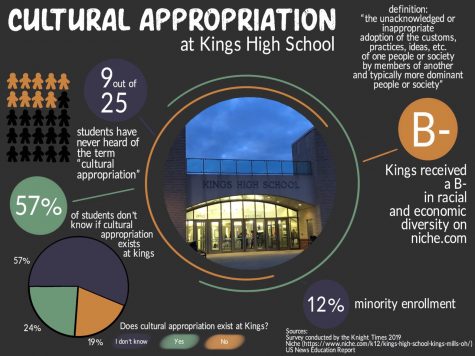

Cultural appropriation: no one wants to talk about it

Samaria Newton, junior, discusses the impact of growing up in a predominately white community, and how cultural appropriate further marginalizes people of color.

Timothy Hicks’s AP Language and Composition wrestles with philosophy, the American dream, and systematic oppression. Hicks talks about these topics in such a way that no student feels uncomfortable. Laughter typically breaks up serious conversations.

Tuesday afternoon’s class was different. Unsettling. Quiet.

Students walked in to two images up on the board: one of Saartjie Baartman, a South African orphan enslaved and displayed at a human zoo in Paris so viewers could look at her physique. The white woman in the photo with Saartjie Baartman is dressed in traditional Victorian fashion mimicking Saartjie’s figure with a full bustle and corset. The other image was a Jim Crow character created by Thomas Rice in 1832.

Hicks explained how Victorian fashion mimicked black women’s bodies even though the white men in power demeaned black women’s natural curves by putting them on display and asking them to perform in private shows. Hick also explained how Jim Crow characters and black face benefited white performers at the time.

Few students participated in the conversation that day, looking around the room desperately for someone to talk. No one knew how to talk about cultural appropriation. What made this conversation so uncomfortable?

Dr. Katherine Borland, Comparative Studies professor at the Ohio State University and the Director of the Center for Folklore Studies says mentioning the topic of appropriation is followed by discomfort because people aren’t aware of what cultural appropriation means, or why it’s considered insulting to some.

“Cultural appropriation is the misuse of a culture that you in reality have no ties to,” Borland says.

The line between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation confuses people, including those who aren’t purposely being offensive or inconsiderate.

“Suppose you are white and you go study abroad and you’re living in Mexico and you’re learning Spanish and they take you to a festival and teach you to dance. Here there’s pretty strong contact with the people, so this isn’t appropriation because the strong connection between you and the people is there,” Borland says.

Borrowing another group’s cultures and traditions is not necessarily a bad or offensive thing. The factor that determines appropriation is all in the way the person goes about borrowing.

“The Cleveland Indians is a good example. From the perspective of the fans, they’re honoring these people. From the perspective of the group [Native Americans] it is a disrespectful caricature, but who gets to decide if it’s cultural appropriation? In folklore it would be whoever is in the marginalized group and who holds the lesser power, and a lot of people aren’t aware of this,” Borland says.

The lack of education around this topic is one reason mentioning cultural appropriation can cause hysteria. Once we begin to educate ourselves, however, the real debate centers around what steps we can take to reach a more progressive mindset.

“That’s not to say we want to police groups of people. It’s also not saying you can’t explore groups. You don’t always have to dress and look white or dress and look black, but there are ways that people can borrow and learn from one another. You just need to learn from people that are from other backgrounds,” Borland says. “Come to a consensus, don’t just claim the right to do whatever you want.”

Borland wants people to think about the past before they feel free to borrow from other cultures.

“You need to understand, however, that although people are now considered equal, these dark and racist histories are not something that can always be washed away,” Borland says.

Mike Stevens, American history teacher agrees with Borland. Stevens was able to use his teaching experience from Mt. Healthy to educate students at Kings who might not be as informed when it comes to things like cultural appropriation.

“I think it really just comes down to lack of knowledge,” Stevens says. “I’ve heard some good kids say some insensitive things just because they don’t know they’re being offensive. And it’s all because we as teachers don’t really know how to approach the situation without treading lightly.”

Stevens has witnessed a fluctuation in the high school’s diversity throughout his career, and the effects that the increase or decrease in diversity has had on the student body.

“I’ve been working here for over 20 years now, and although we’re pretty white we’ve gotten a lot better,” Stevens says. “In my whole career here we are the most diverse we’ve ever been and I feel like that’s a big step in educating people about problems like cultural appropriation.”

Samaria Newton, junior, has become numb to the effects of cultural appropriation.

“Growing up in predominantly white and ignorant schools, I’ve grown to not let it bother me. Kids always grabbing, touching, or pulling at black kids’ dreadlocks and/or braids. Mocking accents, or picking apart voice differences,” Newton says.

For Newton, growing up in Kings has been challenging.

“I have had people in the past who have adopted slang, but yet have made rude comments about me saying ‘bruh’ or ‘y’all’ or ‘talm bout.’”

Sophia Jeng, sophomore, speaks openly about issues of diversity and cultural appropriation.

“Now, when I see students at school, or at school related events, like games, I began to notice the attire my white peers would wear. An outfit that consists of a durag, fake grill, chains, bandana, low hanging shorts, typically a shirt with a rapper like Tupac and accompanied by a ‘hood’ accent,” Jeng says. “Clearly the intention is to portray a hood or gangster black man. Now I’m not saying that students don’t have the right to own these items, although I begin to question the intention once the complete attire is put on and the character comes out.”

The emotions and feelings behind cultural appropriation tends to lead to more discussion about things like racism. The more people are willing to talk about appropriating out in the open, the less likely miscommunications are to occur. Hicks hopes to expose these issues and erase some of the stigma surrounding discussion.

“Our world has been built on ideas that are being borrowed and continually exchanged. As a Language Arts teacher, I see the synthesis of images from other artists as a part of a healthy practice; examining and replicating ideas from other people, cultures, and spaces in the classroom is a great way to learn,” Hicks says. “When done in a respectful and thoughtful way, it can spread understanding and awareness, while reshaping misconceptions and stereotypes. Education that should have existed for decades, and perpetuated by mass media.”

Want to show your appreciation?

Consider donating to The Knight Times!

Your proceeds will go directly towards our newsroom so we can continue bringing you timely, truthful, and professional journalism.

Kayla Estrada is a senior and has been attending Kings since the first grade. This is her second year as Editor in Chief of the Knight Times and she intends...

Carlie • Dec 17, 2019 at 3:34 pm

awesome job kayla! i’m so happy to see you and the others bringing this topic up.

DeAyra • Dec 16, 2019 at 8:23 pm

I love this so much, I just wish the kids were willing to learn more about it.