Eliminating mental health stigma

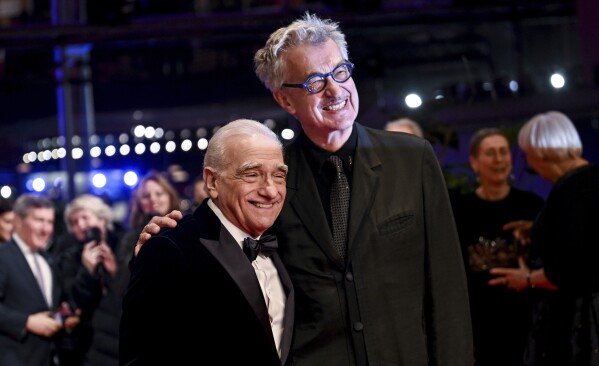

Mia Ridenour, junior, is ready to face the school day despite her anxiety.

December 16, 2019

It all starts when you oversleep. You wake up fifty minutes past your alarm because you stayed up late to complete your homework. By the time you manage to get dressed, brush your teeth, leave the house and arrive at school, it’s two minutes until first period. You try your best to get to your locker and down the hall to your classroom, but to no avail. The bell rings just as you close your locker. Most of your classmates would just move their feet to get to class as quickly as possible without missing too much, but you can’t even fathom that. Your stomach starts to ache. Your heart races. Your feet are rooted into the ground. You can’t focus on anything. Just the idea of having the class’s eyes on you as you walk in is too difficult to handle. What if they hate me? So, instead of heading to class and facing the potential judgement, you just walk away.

This is the reality of anxiety presented by teens in the independent film, “Angst,” shown to the student body on November 6th. Mia Ridenour, a junior, has struggled with her own mental health over the years. In the fifth grade, she dealt with intense anxiety. She even had to see a chiropractor often due to how high she held her shoulders. If she forgot to do an assignment, she would lie to her teachers saying she left it somewhere, because in her mind that made her more “virtuous”. Moving from private to public school in the sixth grade made her relax a bit, but that wouldn’t be the last time she dealt with her mental health.

“When I was thirteen, I saw my grandma pass away in front of me, by myself, due to an accident,” Ridenour says. “I got PTSD, not in the form that they talk about on TV with the whole, you think you’re there and you feel it intensely. It’s more like…it just sort of magnified my anxiety and I would draw ties from what I was doing back to that.”

Through her many years of dealing with anxiety and other disorders, Ridenour noticed a trend.

“My anxiety manifests more in school than out,” Ridenour says. “Just…a constant feeling of I’m wrong and second guessing.”

Anxiety is a disorder many people are familiar with. According to the Child Mind Institute, one in three adolescents will meet the criteria for at least one anxiety disorder before they turn 18. This has more than doubled since the 1980s, when most of today’s adolescent’s parents were in school. With the increase in mental health concerns among those under the age of 18, schools are feeling more and more pressure to support their students who are struggling with various issues.

In order to combat the increased impact of anxiety in the classroom, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) released a new strategic plan in 2017. The plan, “Each Child, Our Future,” ensures that students are challenged, prepared and empowered for their future. The plan includes four domains: foundational knowledge and skills, well-rounded content, leadership and reasoning, and social-emotional learning.

Guidance counselor Erika Volker believes the administration is taking the right steps to fulfill ODE’s strategic plan.

“We’re lucky to work in a school district where mental health has come to the forefront of the things that we really want to do to help our students,” Volker says. “There’s a lot of students who are aware of what mental health is, and are starting to be aware of what we offer to help support mental health awareness for other students and for themselves.”

One of the initiatives the school has taken includes the creation of a social emotional coordinator. Kim Sellers, who took the position, has a whole stack of responsibilities on her plate. She looks at the multi-tier structure support plans to meet the emotional needs of students, works on culture competency, sits in on IEPs when asked, attends to expulsion hearings when mental health is concerned, and meets with students individually, just to name a few. Guidance counselor, Heidi Murray, says that Sellers has been a great resource to her and the district.

“She just has this wealth of knowledge about what the biggest concerns are and how to address them. She’s been a great resource to me, in kind of thinking about what we have in place and what our priorities need to be and what we need to help kids gain,” Murray says.

Sellers feels that mental health has become a crisis.

“For example, the rates in Ohio alone. Suicide is now the first leading cause of death between ages 10-14 and it’s the second leading cause of death with ages 15-34. From 2007 to 2018, our suicide rate has doubled,” Sellers says. “A lot of the pressure that I think today’s adolescents have, it’s a lot greater than I think it ever has been.”

In December 2018, it was announced that Kings was partnering with the Greater Cincinnati Grant Us Hope Organization to bring the Hope Squad to the school district. This peer-to-peer group was created by Dr. Greg Hudnall in Utah back in 2005. Hudnall was working at a school that was seeing one to two suicides a year. It was New Years Day, and he got a phone call from the police asking him to come identify the body of a teenager who took his life in a park next to the school. After Hudnall was able to name the victim, he went to his car and cried for half an hour. That’s when he knew he couldn’t let the students and the administration continue like that. With help from other principals, superintendents, and mental health organizations, he created what was called Circles of Hope. However, something was still missing. What they found was that almost every student they had lost to suicide had told someone, but then swore them to secrecy. Not wanting to betray their friends, the person didn’t tell. Hudnall realized that you could have the best programs in the world, but if you don’t know who to help, it will never be effective. By bringing the students into the equation, the school could teach them to recognize the signs of suicide and depressions and report it to an adult that can help. Thus, the Hope Squad was born. That school district went from experiencing one to two suicides a year, to not having one in over a decade.

The implementation of a program like Hope Squad is something that high school teacher and Hope Squad leader Margie Coleman believes was a long time coming.

“We have talked for years that we need to do better teaching our kids coping skills. We have heard of suicides, not as many from current students, but then we would get stories from kids who recently graduated. We were just always searching for that way to help kids find hope,” Coleman says. “Rates of suicide amongst young people are increasing nationwide, in general, so we just want to try to get the help to kids as soon as we can.”

Although Kings does not see a suicide rate as high as the school where Dr. Hudnall worked, Hope Squad leader Lisa DeBord hopes that Hope Squad can prevent the deterioration of students’ mental health.

“The worry we have as administrators, teachers, parents, is that that’s going to become detrimental,” DeBord says. “Why wait until we have problems to be proactive about these problems?”

DeBord had her own fair share of mental health struggles in high school, namely depression, following the passing of her father. At her school, however, she neither received support, nor did she have any conversations with her teachers or her counselors. The whole plan with Hope Squad, and other measures the school is taking, is to make a more welcoming space for students to talk about those topics that at one point, people chose to be silent about.

“We really want to make sure that students, adults, realize you have have those conversations and its important to because we all need help and that’s okay there’s nothing wrong with that. We’re trying to release that stigma that it’s not okay to talk to someone if you’re struggling,” DeBord says. “We’re teaching these to Hope Squad members, but then our hope is that Hope Squad members are teaching these to their peers and to their peers. It’s just that trickle effect. The more people that have that knowledge, the more people that are learning, the more people can help everyone.”

Now that Hope Squad has been brought to the district, members like sophomore Meredith Viox are looking forward to helping their peers.

“I’m glad that I can help my peers and I think it’s going to do a lot of good,” Viox says. “I want to be able to put myself in their shoes and walk with them and have empathy for them.”

Ridenour believes that Hope Squad is a good step in the right direction. She is worried, however, about its effectiveness.

“If we’re truly going to invest in the Hope Squad […] we need people to feel like they can come forward,” Ridenour says.

The next step the school took was the introduction of advisory, a thirty minute period that occurs every other Friday, starting at the beginning of the school year. The idea was to give kids a break where they can discuss a topic that won’t be on the state report card, but that principal Doug Leist finds just as important.

“It’s focusing on the whole child,” Leist says. “I think we do a much better job of having an open mind to what education is about. I love the fact that we can provide help and services to students, especially in the area of mental health.”

When it comes to deciding the topics that are discussed each time in advisory, Leist turns to the counselors and teachers to learn what they have heard from students, either in conversations or through surveys. Next semester, student organizations such as the Culture Club, RAISE team, as well as Hope Squad, willing be giving presentations.

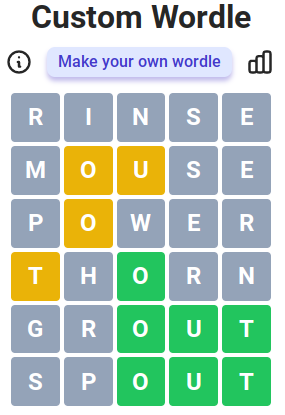

Next, Kings joined the many schools in the region with showing the film, “Angst.” This movie used the classroom example provided earlier as a way to show how common anxiety can be.

“I had a conference call with the producer, twice, before we showed this,” Sellers says. “Her son had anxiety so bad he had to be hospitalized for it. It almost took his life. She then, because she was in this industry, wanted to create something around this for awareness.”

After the viewing of the film, some of the feedback that the counselors received was great, but other students like Ridenour found it to be too simple and narrow-minded.

“That movie, yeah, it scratched the surface, but that movie also implied you have to have panic attacks in order to have anxiety. It also implied you have to run away from your problems if you have anxiety,” Ridenour says. “Personally, I would hate [arriving late to class], but I’m going to walk in front of that class and I’m going to sit my butt down in my seat because my fear of failing at school outweighs my anxiety that Karen in seventh bell’s gonna hate me.”

When asked for her take on Ridenour’s statement, Murray says she agrees, but she also believes that in order to reach the most amount of students in the most effective way, it has to be surface level information.

“Everybody is very different. So how do you go in depth without missing a large group of people who don’t experience anxiety that way,” Murray says. “We do the best we can.”

To help students cope with their anxiety, depression, or any other mental health issue, Sellers has a few suggestions for simple things students can do. She suggests brain breaks and cell phone breaks, as well as another seemingly simple action: sleep. She even refers to it as the “most underutilized coping and health resource” that is available to us.

On an everyday basis, there are multiple options offered in the guidance office to help students through rough patches. One of which is mindfulness cards, which asks different questions such as “what holds you back from living at your highest potential” or “what inspired you today?” Their purpose is for students to forget whatever may be bothering them for a few minutes.

Ridenour has her own routine that she goes through when she’s stressed. “I’m a strong believer in you need to relax every so often,” Ridenour says. “Being able to tell myself, ‘does it really matter in this moment? Is it gonna matter next week?’ Most of the times, the answer is no, it’s not, and I’m able to pull myself out of that headspace.”