All my feminist friends are white.

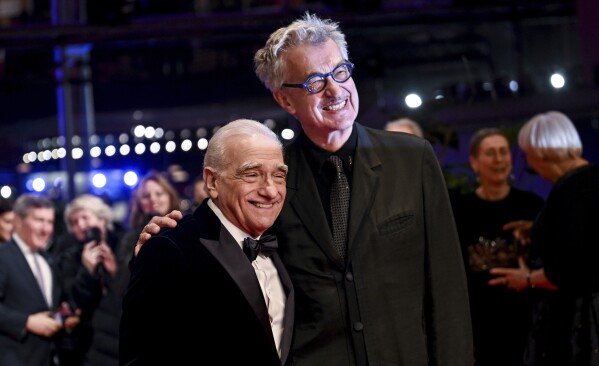

Feminism without intersectionality is damaging to the movement for racial equality. Pictured: (LtoR) Haley Loveless, Jayda Carr, and Allison Escamilla.

April 27, 2021

I declared myself a feminist one evening at the dinner table. Through a mouth full of meat and potatoes I abruptly announced, “I am a feminist because I am tough.” And it was then, at the ripe age of 11, that I managed to turn my conservative dad’s weekly migraines into a daily occurrence, and his newly developing grey hairs were not just a result of my poor table manners.

I remember going to bed that night. Beaming. Dreaming through my head of a world where the neighborhood boys would let me play kickball with them. A world where ugly easter dresses were outlawed and pants were mandatory. Everything seemed so simple.

I was confident in my decision then.

But now I’m not so sure. Now I’m confused.

6 years later, I stormed down my basement steps in a frenzy, defeat painted, the whole world crashing down on me. Women’s History month had taken its toll, and no amount of tone-deaf, pastel Instagram posts created by my white peers were going to change that.

My dad looked at me, secretly hoping I didn’t want to rant and asked what’s wrong. But his hesitance quickly turned to shock the moment the words left my mouth.

“I don’t even know if I’m a feminist anymore.”

Earlier that day during lunch, a white friend of mine had started talking about gender-based discrimination and feminism. This was the first conversation of many that I would endure, due to it being Women’s History Month. She talked about how she was fighting against “get back to the kitchen” jokes and “you throw like a girl” comments between bites of her carrot sticks. Is that what being a feminist means? At that moment, I knew exactly how my dad must’ve felt 6 years ago; because I had absolutely no idea what she was talking about. Her encounters with sexism were unrecognizable to me.

I had been championing women for the majority of my life. Witty comebacks and outspoken advocacy had become my trademarks. My life had been dedicated to fighting for feminism, so Women’s History Month should’ve been my Christmas morning. However, 1 week into March and I realized that my friends’ feminism had no room for brown girls, and no space for me, a young Hispanic woman, attending an 83% white school. It made sense why white women were always at the center of their advocacy. It made sense why I had spent years thinking I didn’t fully comprehend the term sexism. I had never been asked to make a guy a sandwich and I wasn’t athletic enough to give a throw worth judging, but now I realized the sexism my friends experienced was completely different from mine. They were the ones who didn’t understand. Their whiteness filtered their oppression. My brownness amplified mine.

My friends didn’t know about that.

Freshman year, I refused to wear my glasses. Every time I wanted to see the board, I was bombarded with Mia Khalifa comparisons. Not many 9th grade girls want to be compared to a generation’s favorite pornstar. Khalifa herself is aware of the comparisons. Her Instagram bio reads, “Are you even a brown girl with glasses if you haven’t been called Mia Khalifa?” My friends weren’t half-blind freshman year, pleading with teachers to let them move to the front. They wore their glasses freely and shamelessly. But not me. I couldn’t see the board without being reminded of my breast size. Bend over and slut played in my head like a broken record. Mia Khalifa is great, but as an insecure bookworm, I just wanted to be left alone. To this day invasive men follow me to my car after work, they grab me, poking and prodding as if I’m theirs for the taking. Drunk, guy friends reach their hands up my skirt, my squirms and “no’s” never deter them. When a hand goes too far, and my warnings turn to action, I’m met with a smirk and a phrase that makes my blood run cold.

“You’re just feisty, aren’t you?”

While all women understand the fear of the assault, not all women comprehend the backlash of racial stereotypes. Standing there scared and degraded, your attacker acts as if your rage is caused by your ethnicity as if my well-deserved anger courses through my veins because I’m Mexican. I’m not “just feisty.” I’m angry. And I’m sick of people pretending I’m not entitled to the very rage that they’ve created.

My friends don’t know the first thing about that.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month and my Instagram page has been filled with upbeat, flowery posts. The ones that scream, “Look at me! Look at me!” In bright pink letters, I read over and over again, “1 in 4.” But what about me? What they fail to tell you is that this is not the case for women of color. For Hispanic women, it is nearly 1 in 2, and for Native women, it is 2 in 3. Their arrogance to race has given me this false perception of safety. Every too-close-for-comfort encounter with entitled men, every thought of I’m next, has naively been comforted with, it’s only 25%. In reality, my chances are doubled. My aunt’s chances are doubled. My Abuelita’s chances are doubled.

My friends wouldn’t know anything about that.

I am far too familiar with arrogance. Shortly after starting a new job, a fellow waitress was telling me about how “scary” Hispanic men are, because “they’re just obsessed” with her. Meanwhile, my father, while growing up was followed home by police officers every day after school for 4 years. My Abuelita feared for the worst every time her little boy walked out the front door. Hispanic men are seen as threats to society because white women have the power to weaponize their femininity. She didn’t even think about how that might offend me, or come off as problematic. She failed to see our differences while she was insulting my community, yet had no problem stretching to find commonalities in our womanhood. “You know how it is, they’ll be working outside on the new apartments by my house (the Hispanic men), and it can be terrifying leaving at night,” she says to me with a straight face. “Being a girl can just be so risky.”

I later found out she is minoring in Spanish. And rage consumed me.

My friends don’t know the first thing about that.

I listen to my brunette friends whine about “blondes having more fun,” while brown and black girls weep at their own reflections, crying over not meeting a beauty standard that was never meant to include their complexions, never meant to include my complexion–wide noses, narrowed eyes, and textured hair labeled as “ugly,” women of color stripped of any and all femininity: Serena Williams and Michelle Obama compared to men, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez hated for her assertiveness, all while women like Nancy Pelosi and Taylor Swift become the faces of the feminist movement. I dread Summer, or as I like to call it, Hey-look-I’m-tanner-than-Kayla-season. For years I was mocked. Even close friends called me Dora as a joke. They made fun of me for the size of my nose, compared my skin to dirt. Last week was prom, and those same friends now lather their skin with tanning oil. Apparently, ethnic features are pretty on anyone with pale skin. The very melanin I was bullied for having, fills the shelves at the grocery store, only this time in a bottle. Why should I put up with racial oppression for a tan, when they can just buy it for $10 at target?

My friends don’t know anything about that.

I’m older now, and these experiences have given me a new perspective on what it means to be a feminist. I used to spend my days obsessing over the small battles. Now, I’m demanding more. Now, I’m not afraid to address the problems within the feminist community. My friends continue to fight for kickball rights and pants while turning a blind eye to their own racist behavior. White women can be damaging to minority communities because white women still hold privilege. Their womanhood does not exempt them from acting as the oppressors. Whiteness filters oppression, brown and blackness amplify it. White feminists prioritize their comfort. I am forced to prioritize my safety.

My friends don’t know the first thing about that. Because all my feminist friends are white.

Stacie Belfrom • Apr 29, 2021 at 5:32 pm

Kayla, what a wonderfully written article. These are the perspectives that need to be shared so we can continue to show our community at large why these discussions matter. Thank you for your candor.

adviser • Apr 29, 2021 at 11:31 am

Lori Hardaway, I am more than happy to respond. Is there anyway you could provide some clarification as to what you mean? I would love to answer any questions you have, I just need some specifics.

Lori Hardaway • Apr 28, 2021 at 7:00 pm

Could you please share more your experiences outside of Kings Mill? Cincinnati? Your travels. This rings of your walk while growing up, though have you explored the other cultural dynamics at play. Thanks.

Jan Middleton • Apr 28, 2021 at 2:26 pm

What a powerful article. Thank you for sharing your insights-this was very eye opening for me!

Great job!