Ideas can’t be banned

Teachers push back against book challenges

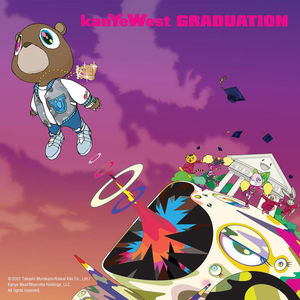

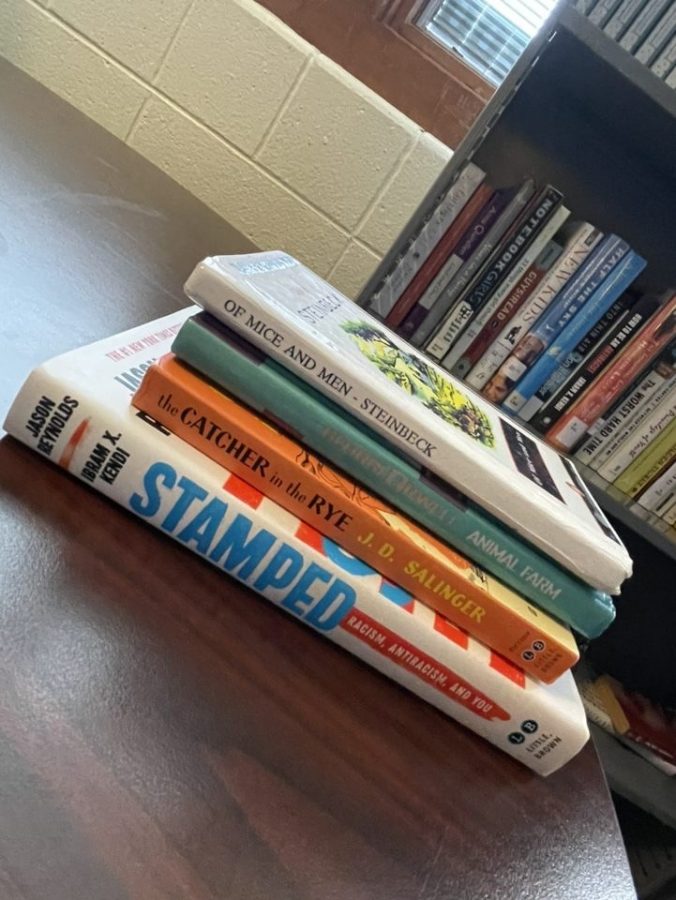

A stack of books including novels listed in ALA’s Top 10 Most Challenged Books.

A rash of book bans and challenges sweep the nation in conjunction with laws being passed to restrict certain topics from being taught in the classroom.

Katie Isaacs, a ninth and tenth grade English teacher, disagrees with the philosophy of banning books from curriculum due to one insensitive scene or chapter.

“I think a lot of the reason why books get brought into question are because people focus on passages,” Isaacs said.

Isaacs noticed that when books and their role in the curriculum are challenged by community members, there is too much focus on individual pieces of the book rather than the story as a whole.

“These larger works are never meant to be focused on in parts,” Isaacs said.

One book on the American Library Associations Top 10 list of challenged books is “Of Mice and Men” by John Steinbeck. This book is often challenged because it presents inappropriate treatment of women.

“If you remove [the treatment of the wife], then you remove that aspect of the culture that Steinbeck is trying to get us to see,” Isaacs said.

High schools around the country are banning books that are on the national list of challenged books simply because of complaints.

“The situation in the book is inappropriate. It’s not inappropriate for me to experience that if it’s leading me to a theme,” Isaacs said. “If I don’t talk about [the theme], I’m not talking about the book. I’m talking about the segment. That is not the book.”

Not only would students miss the theme of the book, but also they would miss the benefits that come from reading and learning about such heavy topics.

“To the core of my being, I will always support my students reading things that have situations in them that we might not agree with, that we might find disturbing, because there’s growth in that,” Isaacs said.

By focusing on the growth that one can experience from reading these books, we see our own biases and opinions shine through.

“If you look at a painting and say ‘this painting offends me,’ I feel like it says more about you than the actual painting,” ninth and tenth grade English teacher Ryan Weber said.

Junior Sammy Patterson feels like though these books talk about sensitive topics, the historical value the students receive from reading them is worth it.

“I don’t think it’s heavy because it happened. It’s real. You can’t really change that,” Patterson said.

Students and teachers want to be able to read books and learn important lessons from them.

“A lot of people are trying to ban these books because of history,” Patterson said. “But you can’t really change history.”

Books like “Of Mice and Men” that are currently on banned book lists have been in the Kings curriculum for decades with no challenges. The district has a policy in place for adding new books to the curriculum and for challenging books currently used in the curriculum.

“Typically when we’re looking to adopt something new, it generally starts at the teacher level,” Director of Learning and Education Matt Freeman said. “So, the teachers find a resource that they want to use to help them to illustrate and teach particular standards in the curriculum.”

There are a series of steps that Freeman takes before he introduces the resource to the Board of Education for approval.

“With a novel, we have a specific process that we use. So we form a committee that reads the book, [and] we have other teachers read the book. We do cross-curricular, so we have [a teacher] not in English read the novel, and then teachers above and below the grade level for the chosen book. Then we have a form that teachers fill out,” Freeman said.

Getting a resource removed from a curriculum has a similar process.

“A community member would contact me and then there’s a form that they actually fill out that kind of outlines their objection to the resource and they give that to me,” Freeman said. “Then the board policy says that I would form a review committee, and that review committee would look at the complaint, review the resource again, then make a recommendation to the superintendent for it to either stay in the curriculum as a resource or it would be removed.”

Parents have complained about books at recent board meetings, but no formal objections were made with the proper paperwork.

Professor Daniel Rivers, a professor of American studies and literature as well as the director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies, commented that the act of banning books is a way to censor our past.

“When I come to this as a scholar, I see it is as a hostility to archives,” Rivers said.

Teachers use these resources in class in order to analyze the text, not to use them as a free read for students.

“In a classroom I’m not just tossing a book at you and walking away, like, we’re looking at the historical context, we’re looking at what the circumstances of race were at that time in the nation,” Rivers said.

Overall, the principle behind banning books is flawed and cannot come to our community without consequence.

“We do have a long precedent of trying to use book banning and book burning to suppress certain kinds of thinking,” Rivers said. “I don’t think you can ban ideas, and I think that’s why people ban books.”

Want to show your appreciation?

Consider donating to The Knight Times!

Your proceeds will go directly towards our newsroom so we can continue bringing you timely, truthful, and professional journalism.

Amelia is a junior and the News Section Editor for The Knight Times. She chose to become a staff writer and editor to help connect the community through...

Hello, I am Ryan Flecker, section editor of the Arts and Entertainment crew for The Knight Times. As a senior, my favorite aspect of being a section editor...

Isaac • Feb 21, 2023 at 1:54 pm

This is actually a really new and interesting way of looking at it. Thanks!